Pilgrim’s progress is crawling towards the installation of the primary DC electrical wiring. The primary wiring components are:

- Battery Bank(s)

- Large gauge, high amperage wires connecting primary components

- Shunts to allow for the installation of battery monitors

- Switches for directing or cycling on/off the flow of power through primary wiring & components

- Bus Bars to make multiple wire connections in which all the wires are on a common circuit.

- Terminal blocks to make multiple wire connections in which the wires are on separate circuits.

- Terminal posts for making connections in which the wire(s) are on separate circuits.

- Fuses to protect the wiring and components from excessive amperage.

We purchased a BlueSea 600A Power Bar to serve as the primary distribution point for the DC positive wiring. The wiring leading from the positive bus will be fused at the battery box. A few of the other wire runs will need to be fused proximal to the bus bar.

Simple Diagram of Pilgrim's Primary 12V DC+ Distribution Bus

We are installing ANL Fuses for Pilgrim’s primary wiring system. Rather than purchase individual ANL fuse holders for each circuit requiring a fuse “downstream” of the positive bus, we are fabricating our own ANL Fuse Block.

Materials used to create DIY fuse block clockwise from top: Starboard, BlueSea Bus, ANL fuses, 5/16" Stainless Steel Fasteners.

Our fuse block will utilize a ¼” thick Starboard™ base to mount the BlueSea Bus adjacent to a DIY terminal block. The gap between the bus and the terminal block will be set up to accommodate ANL Fuses. ConFUSED yet? Hang in there pictures are worth a thousand words.

Our DIY terminal block will consist of ¾” Starboard™ with 5/16” countersink machine screws as studs.

Laying out the spacing for the 5/16" countersunk holes.

The holes in the ¾” Starboard™ are positioned to match the alignment of the BlueSea bus bar. The holes are drilled and countersunk to fit the 5/16” machine screws.

Inserting the 5/16" machine screws in the starboard block.

The screws are inserted from the underside of the block with the threaded portion of the screw exposed on the topside. A washer followed by two nuts jammed against one another secure the screws to the Starboard™ block.

Inserting a couple ANL Fuses between the new block and the prefab bus ensured proper positioning when we mounting the two pieces on the base.

Completed fuse block sans the wires and one fuse.

The bus and the terminal block are held in position by #10 counter sink machine screws capped with lock nuts. The base extends ¾” beyond the assembly on each side. This excess base will provides area for mounting screws.

When installed in Pilgrim the fuse block will have large gauge wires and/or an ANL fuse attached to each post.

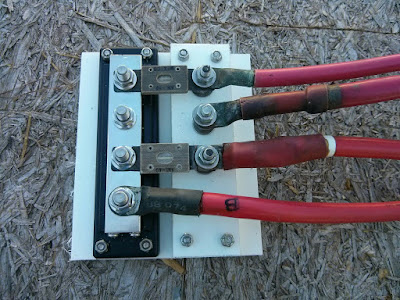

Mock up of wiring attached to fuse block (still missing one fuse.

The image above is a mock-up of the future installation aboard Pilgrim. From the top down…

- The upper wire feeds power from the engine alternator when the engine is running.

- The second wire (currently missing an ANL fuse) runs to a BlueSea Systems Automatic Charging Relay (ACR). The ACR charges the starter battery when voltage in the circuit is between a preset range. The ACR also isolates the house bank during engine starting.

- The third wire feeds power to our battery & bilge pump management panel. Here is a link to our previous post: Installing the New Battery & Bilge Pump Management Panel – June 28, 2015

- The lower wire (labeled “B”) runs to the house bank of batteries. This wire run is fused proximal to the battery bank.

After reviewing the installation manuals for the BlueSky 2000E PV Solar Charge Booster, the AirX Wind Generator, and the ProNautic 12.40 Battery Charger, Pilgrim’s DC+ wiring schematic continued to evolve. The DIY ANL Fuse Holder (see previous post) needed to double in capacity.

Original Fuse Block Design:

Updated Fuse Block Design:

I disassembled the original fuse block; doubled the size of the base; and added a second row of terminals.

Expanded DIY ANL Fuse Block

The missing fuse feeds the Battery & Bilge Pump Management Panel. We are still figuring out the correct size fuse for this circuit.

Eager to check out Pilgrim’s DC wiring schematics? I do plan on posting the wiring diagrams after a few “outside consultants” review my plans.

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Fabricating a DIY ANL Fuse Block

Jeff and Anne continue with their thorough refit of s/v Pilgrim. Here they tackle the fusing of the primary wires in the 12V electrical system. And they do it right. Jeff made this as two separate posts, I have collapsed them into one here.

Labels:

electrical,

s/v Pilgrim

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Bimini Renewal

This post originally appeared on Windborne in Puget Sound as a series of three posts; they have been collapsed into a single, longer post here.

One of the things about owning a boat for a long period of time (or ageing in general, for that matter...) is that you get to see the effects of time. They are almost never kind. But to avoid becoming morose, let's keep this focused on Eolian's cockpit canvas.

Way back in 2003 we had our cockpit canvas renewed by Barrett Enclosures in Seattle. They did a masterful job. But that was 12 years ago. In the intervening years, I have had to redo almost all the stitching (because I made a short-sighted decision to use the somewhat less expensive "UV Stabilized" polyester thread instead of the Teflon thread), refresh the Sunbrella's waterproofing on an annual basis, and deal with slow but inevitable fabric shrinkage. It is a sad thing to me to see the sorry state that things have reached, from such initial beauty. So, it is time to do that "once in a lifetime task", a second time. New cockpit canvas is needed.

But this time, instead of investing more than ℬ6.500, I decided to give it a try myself. Already having a Sailrite LSZ-1 makes this a possibility. So I reviewed Sailrite's excellent online videos, ordered a bunch of Sunbrella, fittings, and notions from Sailrite, and set to work.

After uneventfully patterning the aft bimini panel, I encountered the first problem: There was no place on the boat large enough to lay out the pattern on the cloth. We were able to get about 3/4 of it on the cabin top, so we did that and then folded the marked section up enough to get room to finish. Yes, I know that this process was fraught with opportunities for errors to creep in. But within the tolerance that we were working with (about 1/8") I think we did OK.

But there are a lot of fabric pieces involved in the aft panel. Altogether 7 more pieces were needed, besides the obvious big one. And then the space thing reared its head again. Working with the LSZ-1 on the edge of the saloon table, I was able to sew the long seams by letting the completed section pass over the table and then off the far edge, on its way back to the floor.

On a project like this, fabric management is always difficult, especially when working in a limited space (tho not as big a problem as this). My recommendation: always, ALWAYS use seam-stick tape, 3/8" for normal seams and 1/4" for zippers. It is a lifesaver. And don't be in a hurry.

This last weekend, I finally got the last of it done and installed it. But sadly, somehow I managed to get the locations for the Common Sense fasteners for one of the aft side curtains off slightly. Rather than make another set of holes in the new piece, I am going to relocate the eyelets in that side curtain instead. The thinking is that the side curtain is old and will be replaced anyway at a time in the future much nearer than the just-completed panel. And because of this, I am not going to show you a picture of it. Yet.

The plan is to move ahead with the other roof panels in sequence - the loose center panel that connects the dodger to the bimini, and then the top panel of the dodger. When redoing the top panel of the dodger, I will be revising Barrett's design, making the top panel and the front panel separate pieces - the thing is just too unwieldy for me to handle as a unit. And in fact, it looks like Barrett made the roof and front of the dodger separately, and then stitched them together as a final step. I will use Common Sense fasteners to hold them together instead of stitching.

So. I can say at this point, nearly 1/3 done with the top of the bimini and dodger, that with Sailrite's instructional videos, their tools and their materials, this is a doable project. It is complex and requires constant attention to detail, but it is doable by the cruising sailor, at a savings of 90% over the cost of having a professional do the work. But don't figure on getting it done over a weekend...

OK, as promised, here is the result. I am one third done with redoing the bimini and dodger. That is, I have completed the bimini roof (I am excluding the side curtains and the dodger front from consideration at this point in time - the vinyl is still serviceable, and because these surfaces are not horizontal they have not suffered sun damage to the same extent).

I think it came out pretty good. In fact, it looks about as good as the original did when it was new and before shrinkage pulled everything tighter than a drumhead.

So, can you do this yourself? The answer is yes. But first, I strongly recommend that you view the following Sailrite video: How to pattern a bimini. There used to be another video on the website that took you thru the process after patterning, but they have apparently taken it down. But if this whets your appetite, then get this DVD and study it, thinking thru each thing that is done, and understanding why it was done.

First, nomenclature. In the roof panel I made, there are three major piece types:

As you can see, there are two more panels that need to be reconstructed. And that sail cover is looking pretty shabby too...

A quick revisitation of the tails issue, with an illustration. And then I promise I will shut up about it.

Consider the forward edge of the aft bimini roof panel. Because I am lazy, I originally made the tail as a hang down tail. That is, the tail was a long skinny rectangle - easy to cut, and minimal fabric usage. But because it had no curvature, it did not match the contour of the front edge of the panel. Consequently, after installation it had a scalloped appearance and made a loose fit to the center panel:

What is worse, with Eolian moored facing into the weather, when it rained (and oh, does it rain here in the PNW), the wind blew the rain under the edge of the tail and into the cockpit. In fact the tail acted as a funnel, actually scooping in rain.

So I picked all the seams and took apart the front edge of the panel. And I cut fabric for a new tail, this time a tuck back tail - contoured to match the forward edge of the panel. The result is gratifying - look how tightly it meets up with the center panel! The built-in curvature makes the edge of the tail actually press down on the center panel - wind-blown rain is excluded (tested less than an hour after reinstallation... this is the PNW after all).

So far, I cannot think of a situation where I would use a hang down tail.

One of the things about owning a boat for a long period of time (or ageing in general, for that matter...) is that you get to see the effects of time. They are almost never kind. But to avoid becoming morose, let's keep this focused on Eolian's cockpit canvas.

Way back in 2003 we had our cockpit canvas renewed by Barrett Enclosures in Seattle. They did a masterful job. But that was 12 years ago. In the intervening years, I have had to redo almost all the stitching (because I made a short-sighted decision to use the somewhat less expensive "UV Stabilized" polyester thread instead of the Teflon thread), refresh the Sunbrella's waterproofing on an annual basis, and deal with slow but inevitable fabric shrinkage. It is a sad thing to me to see the sorry state that things have reached, from such initial beauty. So, it is time to do that "once in a lifetime task", a second time. New cockpit canvas is needed.

But this time, instead of investing more than ℬ6.500, I decided to give it a try myself. Already having a Sailrite LSZ-1 makes this a possibility. So I reviewed Sailrite's excellent online videos, ordered a bunch of Sunbrella, fittings, and notions from Sailrite, and set to work.

After uneventfully patterning the aft bimini panel, I encountered the first problem: There was no place on the boat large enough to lay out the pattern on the cloth. We were able to get about 3/4 of it on the cabin top, so we did that and then folded the marked section up enough to get room to finish. Yes, I know that this process was fraught with opportunities for errors to creep in. But within the tolerance that we were working with (about 1/8") I think we did OK.

But there are a lot of fabric pieces involved in the aft panel. Altogether 7 more pieces were needed, besides the obvious big one. And then the space thing reared its head again. Working with the LSZ-1 on the edge of the saloon table, I was able to sew the long seams by letting the completed section pass over the table and then off the far edge, on its way back to the floor.

On a project like this, fabric management is always difficult, especially when working in a limited space (tho not as big a problem as this). My recommendation: always, ALWAYS use seam-stick tape, 3/8" for normal seams and 1/4" for zippers. It is a lifesaver. And don't be in a hurry.

This last weekend, I finally got the last of it done and installed it. But sadly, somehow I managed to get the locations for the Common Sense fasteners for one of the aft side curtains off slightly. Rather than make another set of holes in the new piece, I am going to relocate the eyelets in that side curtain instead. The thinking is that the side curtain is old and will be replaced anyway at a time in the future much nearer than the just-completed panel. And because of this, I am not going to show you a picture of it. Yet.

The plan is to move ahead with the other roof panels in sequence - the loose center panel that connects the dodger to the bimini, and then the top panel of the dodger. When redoing the top panel of the dodger, I will be revising Barrett's design, making the top panel and the front panel separate pieces - the thing is just too unwieldy for me to handle as a unit. And in fact, it looks like Barrett made the roof and front of the dodger separately, and then stitched them together as a final step. I will use Common Sense fasteners to hold them together instead of stitching.

So. I can say at this point, nearly 1/3 done with the top of the bimini and dodger, that with Sailrite's instructional videos, their tools and their materials, this is a doable project. It is complex and requires constant attention to detail, but it is doable by the cruising sailor, at a savings of 90% over the cost of having a professional do the work. But don't figure on getting it done over a weekend...

OK, as promised, here is the result. I am one third done with redoing the bimini and dodger. That is, I have completed the bimini roof (I am excluding the side curtains and the dodger front from consideration at this point in time - the vinyl is still serviceable, and because these surfaces are not horizontal they have not suffered sun damage to the same extent).

I think it came out pretty good. In fact, it looks about as good as the original did when it was new and before shrinkage pulled everything tighter than a drumhead.

So, can you do this yourself? The answer is yes. But first, I strongly recommend that you view the following Sailrite video: How to pattern a bimini. There used to be another video on the website that took you thru the process after patterning, but they have apparently taken it down. But if this whets your appetite, then get this DVD and study it, thinking thru each thing that is done, and understanding why it was done.

First, nomenclature. In the roof panel I made, there are three major piece types:

- The roof panel itself - the largest piece of fabric by far

- The sleeves. These pieces of fabric form the sleeves which zipper around the tubing at the front and rear of the roof panel.

- The tails. These are the narrow strips of fabric that hang down at the front and rear of the roof panel - they serve as the attachment points for the side curtains (at the rear - on mine you can see the rivets holding the Common Sense fasteners) and the center panel (at the front).

- There are also some narrow reinforcing strips that go on the bottom edges of the sides to strengthen the attachment points for the side curtains.

- Use Tenara Teflon thread. I can't recommend this strongly enough. The special "UV resistant" polyester thread will last approximately 5 years (in the PNW - less in the tropics). The Tenara thread will last indefinitely - far outliving the fabric.

- When sewing, use the basting tape that Sailrite sells. The stuff you can buy in your local fabric store is designed to wash out and is a far weaker adhesive. Use 3/8" for most seams and 1/4" for zippers.

- When installing zippers, make sure that they will be covered - that is, protected from the sun.

- Tools - you should buy these tools and consider them part of the cost of the bimini. Your cost will still be far, far less than what you'd pay for professionally built canvas.

- First and foremost, a walking foot sewing machine. You just can't do this work with a home sewing machine. I have a Sailrite LSZ-1 and love it.

- A binder of some type for applying bias edging tape

- This nifty tool set for installing male Common Sense fasteners

- This punch for installing Common Sense eyelets

- Please note that my project did not require installation of snaps, Lift The Dot fasteners, etc. so I have not included tools for their installation here. But if you need these fasteners you should look carefully at the tools that Sailrite offers.

- If you are doing what I did, replacing an existing bimini, you can pattern right over it without removing it. This allows you to get a better take on where the edges need to be, and saves a lot of labor. You should apply the seam stick tape directly to the old bimini without an intervening layer of some other kind of tape. It holds better, and yet can still be removed after the patterning.

- For the panel to install correctly and fit well, it is critical that you consider and think about things like this:

When patterning, the line defining the front and rear seams (where the sleeves and tails attach to the roof panel) should be made, not on the top of the tubing, but rather 90° away on the front (or rear) side of the tube. Doing it this way makes it simple to attach the other edge of the sleeve. Magically, you can just smooth the sleeve flat against the roof panel and stitch the zipper where it lays, without making any allowance for the wrap around the tubing whatsoever. I know that doesn't seem right, but it is. Get out some strips of paper and try it out - I know that I had to in order to convince myself.

If on the other hand you need for the seam to be on top of the tubing (as for example if the seam joins two adjacent roof panels over an intermediate support), then you cannot simply lay the sleeve flat to determine its attachment point to the roof panel. Instead, lay it flat, mark the edge, and then move it back 1.25 inches (I think... get out your paper strips and confirm this number - it will depend on the size of your tubing) and attach it there. Because in this case you do need to account for the wrap around the tubing, and it's a surprisingly large amount.

If you should use a top seam for the forward edge of your roof panel, you will need to make the tail wider by half the diameter of your tubing so that it will extend the desired distance. - You will face a decision whether to use "hang down" tails or "tuck back" tails. Hang down tails are just straight rectangular pieces of fabric; tuck back tails are contoured to match the edge of the bimini to which they will be attached. I initially made mine with the hang down tails, but I was disappointed with the way they, well, hung. Because they are straight fabric pieces, they do not follow the contour of the bimini - they just look bad. I made new tuck back tails, ripped out the seams and installed them.

- When laying out the sleeves or the tuck back tails, the video may encourage you to use the pattern to determine one edge and then laboriously lay out a second line the desired distance away by making a series of markings perpendicular to the original line. This is unnecessarily tedious. Instead, lay out the first line using the edge of the pattern, pull the pattern back the desired amount, and lay out the second line, again using the edge of the pattern.

As you can see, there are two more panels that need to be reconstructed. And that sail cover is looking pretty shabby too...

A quick revisitation of the tails issue, with an illustration. And then I promise I will shut up about it.

Consider the forward edge of the aft bimini roof panel. Because I am lazy, I originally made the tail as a hang down tail. That is, the tail was a long skinny rectangle - easy to cut, and minimal fabric usage. But because it had no curvature, it did not match the contour of the front edge of the panel. Consequently, after installation it had a scalloped appearance and made a loose fit to the center panel:

|

| Hang down tail. Bow is to the left, and new panel is on the right |

|

| Tuck back tail - doesn't that look better? |

So far, I cannot think of a situation where I would use a hang down tail.

Labels:

canvas,

s/v Eolian

Tuesday, January 12, 2016

Fender Washers--Basically Useless?

Drew has been at it again... Here he is testing fender washers as might be used instead of proper backing plates for items thru-bolted on deck. Drew made two posts; I have included both of them here.

In the process or researching an article on backing plates, it seemed worthwhile to actually test some washers. After all, it was the failure of fender washers that led to cracking of my deck and the need to remount the winches.

I used a 3/4" pine board as a surrogate for a cored deck and tightened a collection of 1/4" washers untill the first damage to the wood, and until failure. To no surprise, common washers, fender washers, and HDPE were glaring failures, and FRP and thicker metal washers were fine.

(click to enlarge table)

And then there is always the matter of what happens in wet places. Though I like aluminum for ease of fabrication, I also know its limitations.

As ramp-up for some Practical Sailor testing, I thought I would share a preview.

First, unable to secure scraps of deck material for which I could be sure of the pedigree, I laid up some of my own. The testing will based upon 1/2-inch balsa core with (1) 6-ounce cloth and (1) 17-ounce biaxial layers on the deck side and (1) 17-ounce biaxial layers on the under side.

I drill a 1/4-inch hole (no epoxy plug, block of wood on the back side) and tightened down a fender washer against it. At 10 in-pounds (about 675# load) the washer had distorted and the laminate was failing. for comparison, the bolt working load of a Lewmar 40 winch (1/4-inch bolts) with a strong grinder is about 500 pounds each. In other words, without an epoxy plug the bolt will fail under working load and standard ASME bolting load, with no safety factor for aging and fatigue. It is about 5x weaker than good design suggests. It also explains why I had a PO installed winch rip out.

By 18-in-pounds the fender washer was buckled and the nut was well into the core. For comparison, this is about 50% better than a plain pine board in each case.

I repeated the test with only lock washer. The same result! The fender washer resulted in no increase in strength. The point being, that the bolting washer provided better support in close, the end result being the same.

Testing for the actual project will involve proper epoxy plugs. However, since under the load the bolt will NOT be supported on the other side (the winch or cleat will be lifting) in the real world, the top side support will be supplied by a 4-inch diameter ring spacer, allowing the washer to pull through, if that is what it wants to do. I've tested this without the epoxy plug; not surprisingly, it lowers the failure load and creates top side damage much like I saw on my failed winches.

We'll see. But for now, the moral of the story is that fender washers are basically useless; they fail as soon as they are actually needed.

Labels:

deck,

experiment,

fiberglass,

howto,

maintenance,

Sail Delmarva

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)