The skunkworks deep beneath Stately Jones Manor could best be described as a low-tech production facility for thrifty wood-based solutions to nautical problems. However, occasionally there is a need to solve a problem with the solution.

Like how to make short wood longer.

(Get your minds out of the gutter, folks.)

Or how to drill a bunch of holes accurately and quickly.

Surprisingly, not every tool is available at Lee Valley Tools. Sometimes, you gotta build the solution to your problem. I had a couple of problems like that recently.

The Small Little Boat Company had a small real-money -paying refit job to accomplish over the winter- replacing the gunwales on a canoe. This project presented some unique challenges, starting with the empirical/geometric hurdle of working on a 16' long canoe in an embarrassingly cluttered 15' long workspace.

Once the logistics of the workspace were sorted, the scantlings of the job at hand moved to the top of the challenge list. The canoe required ash gunwales with an uncommon rabbet to conceal the top edge of the hull. Unless the customer wanted to pay biggish money for one piece full length un-rabbeted gunwales and truly rapacious shipping costs to transport the 16+ feet long wood sticks from the Big Smoke to Stately Jones Manor, I was gonna have to improvise.

So, improvise I did.

My local NOSLY (Neighbourhood Old School Lumber Yard, for those of you who don't remember acronyms used in past posts, or AUIPP) stocks local ash, a quickly disappearing stock thanks to the advance of the ash borer, in a variety of lengths... up to ten feet. Time to scarph.

Scarphing, or scarfing, (btw, note to readers: do NOT Google "scarfing" with your safe search off. Trust me) is a technique for connecting two too-short pieces of wood into one that is not, via a combination of mechanical and/or adhesive fastening and tapering the ends of the pieces to be joined, creating a seamless length, like so:

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Simple, right? It is.... except that the tapers have to be EXACTLY (or as close as possible) the same. If the angle or rise:run ratio varies, the piece will look like it has a waist or a belly and will not be straight. So, each end has to match. I have eight of them to cut. The chances of me getting even one correct taper working freehand is zero, so I needed a jig.

Right on time, Good Old Boat publishes an article on building a scarphing jig. Oddly for GOB, it was an article that was difficult to follow with few and poor photos. I thought I could improve on the design, so I set out to build my version.

As is often the case in all things nautical, there is no hard and fast rule to the angle ratio of a plain scarph joint. 8:1, 10:1, 12:1, 15:1 have all been used by somebody somewhere and often the thickness and species of material in question plays a part.. The most common scarphing ratios, however are 8:1 and 12:1, so I decided to build a jig allowing me to make the cuts with my radial arm saw quickly and easily in both ratios.

What does this 12:1 or 8:1 stuff mean?

Glad you asked.

A ratio of 12:1 means that over 12" of length, there will be a rise of 1". A one foot long ramp, would be only 1" high at the end if the ratio is 12:1, for example.

So, to build my jig I grabbed some of my seemingly inexhaustible supply of scrap furniture-based particle board, and cut off a piece a little more than a foot wide, making the 12:1 layout easy.

On one end I laid out a 12: 1 scarph, on the other end 8:1, and carefully marked them so I would remember which is which in the future...

Setting the scarph ratios is simple math. For 8:1, measure 8" along the edge and mark. At the mark measure 1" in, then mark. Use a straight edge to draw your cut line, from the corner extending past your "1" mark. Repeat the process for the 12:1 edge.

Then I cut a couple of pieces of scrap to act as fences along the scarphing edges...

Cut your scarphs and screw and glue your fences in place...

Screw and glue fences on each end to allow clamping to the saw table fence.

Now it is a simple task to quickly cut scarphs every time. Lay the wood against the fence, clamp to the table or the jig fence, slooowwwwllllyyy draw the saw through the wood. Done.

Once the scarphs were cut, the lengths were rabbetted and routed and finally epoxied together into full 17' lengths.

Then they were sanded, oiled, oiled again, sanded, oiled yet again, and finally installed on the hull:

The screws were bunged, the bungs were trimmed,

The whole works was sanded and oiled again, and out the door she went:

Although this jig was designed with a radial arm saw in mind, it could also be used on a table saw, with the addition of t-track to the bottom of the jig, allowing it to slide along the table.

Total time to build the scarphing jig: 40 minutes.

Total cost: $0. If you don't have any discarded cheap furniture laying around and have to buy NEW cheap plywood or particle board, total cost will be under $20.

I'm building a shelf for the hanging locker and I need some pin rail. This is one of the few times in the maritime glossary that the same term has two different meanings, so a little clarification is in order here.

On traditional sailing ships this is a pin rail:

Literally, the rail which houses the belaying pins.

In my case, however, pin rail is a decorative and functional rail installed to boat shelves to prevent the objects stored on those shelves from becoming unstored when the boat moves.

image courtesy of ThaiTeak Marine

Teak pinrail runs about $8-10 per foot.

I don't need teak.

I do need pinrail.

(Not to go off on a tangerine here, but those of you who have been following our seemingly endlessmeddlingimprovements to Whiskeyjack may have noticed the variety of woods used, with nary a mention of that stalwart maritime favourite, teak. Lots of mahogany, some cedar, even some pine, some oak, some ash, but no teak. My personal opinion is that teak below decks is often an unnecessary affectation. The big upsides to teak are it's weatherability and wet traction, neither of which is a big concern above the sole below decks. Note the use of the phrase "above the sole"- teak flooring is an exception, but it's necessity in this application is debatable, in my opinion. There are lots of other choices that will work just as well if not better than teak at a fraction of the cost. And the variety of woods adds a little character. As George Buehler says in Buehler's Backyard Boatbuilding, "I like looking at various wood grains and stuff.." Now, I have managed to scavenge an assortment of teak odds and ends from DonorBoat which may make an appearance in upcoming projects. Hey, I've got it, might as well use it. But I wouldn't buy it.)

Right, so back to pinrail. If I don't want to buy it, I gotta make it. Really, it's pretty simple stuff- some spindles, a top rail and a bottom rail, and a bunch of holes... that all have to be exactly the same spacing on both top and bottom rails.

Okeydoke, time to build a jig.

I measure up my drill press table...

Then I scavenge some more of that old cast-off IKEA dresser that became a mitre saw extension , and I put together a drill press table, about 36" wide and about 8" deep.

I installed a couple of 1x1" x 6" offcuts to the underside of the table as cleats which straddle the drill press table. A couple of small clamps underneath hold the pinrail jig table securely to the table.

Now comes the finicky part.

After measuring the pin rail already affixed to Whiskeyjack, I discovered that the height was a constant 3", the width was a constant 7/8", the top rail was 5/8" thick, the bottom rail was 3/4" thick... and some rail had the spindles on 4.5" centers, others on 3.5" centers. Okay, so if I'm gonna build a jig might as well make a jig capable of building 3.5" center pin rail and 4.5" center pin rail, AND might as well toss in 2.5" center capability too, just for giggles.

So i needed to make an index block. Determine where the holes should be, find the center of the rails, determine the diameter of the spindles to determine drill bit size, etc.

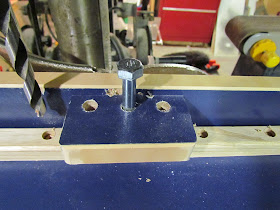

With my index block set, it is a simple matter to drill three holes 1" apart on another offcut piece of IKEA dresser, and screw it to the jig's fence in the proper position as a center-setting block, as determined by the index block.

Drop an appropriate size bolt into the appropriate hole for the center desired to act as a stop.

Making pin rail is easy.

Rip two lengths of wood to the appropriate dimensions, then round the edges with a router or sander.

Lay the bottom rail on the jig table. Butt up the end of the rail with the bolt, lift the bolt and tuck the rail 1/2 way under the bolt. This sets up the first hole exactly on the desired center. If the rail was just butted up against the bolt, that first hole would be off by half the width of the bolt. Not a big deal, but it does waste a little material. Drill the hole, lift the bolt, slide the rail down until the bolt drops in the previously drilled hole.

Keep going until you run out of rail. Repeat the process with the top rail

Sand and install your spindles. Hardwood spindles can be bought in bulk for as little $.20 each, or if you want simpler looking spindles, cut your own out of dowel. I bought the ones pictured below. I couldn't MAKE them for what they cost- twenty two cents a piece.

Total time to build the jig and make the rail shown above: 3 hours.

Total cost: $0 for the jig, $3 for the spindles. If i had to buy the wood and the bolt to build the jig, material cost would be under $20.

...Unless you use teak.

This jig could also work with a hand drill, with one important modification- enlarge the center -setting block to incorporate a drill guide. In other words, build a block with one hole for the drill bit, and three more holes 2.5", 3.5" and 4.5" to the right for the stop bolt.

Life aboard is living large, in a small space. Every boat owner has found ways to make life in that small space easier, more comfortable, more convenient. The idea behind this site is to provide a place where these ideas can be shared amongst the boating community. To participate, send your contribution to SmallBoatProjects at gmail dot com.

Pages

▼

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Jigs

I have said it before: The really good wood workers don't just make things, they make tools - a high profession indeed, and one we should all learn from. Over at Dock Six, Brian has been at work and gives us two excellent examples:

No comments:

Post a Comment